Visualizing

the Virus

Making the Invisible Visible

Unequal Histories

I wrote this essay in June 2020, when it was still unclear that the COVID-19 pandemic would be such a long one. It was written as a way for me, as an art historian with a commitment to social and political justice, to grapple with questions of scale, representation, and unequal histories. It sowed the first seeds for the current Visualizing the Virus project.

The essay argues that seeing is political and that the act of visualizing the virus during the current pandemic has been both panacea and political tool – depending on who does the visualizing. It was fuelled by Boris Johnson’s Coronavirus slogan ‘Stay Alert, Control the Virus, Save Lives’ and by Donald Trump’s repeated reference to the ‘invisible enemy’; and also by the grim relationship between the use of tear gas – a potentially dispersible and invisible weapon – in Black Lives Matter protests, and Covid19’s disruption of the universal right to breathe, which exposes histories of structural racism.

Swarna Chitrakar with her Coronavirus scroll. Photo supplied by artist.

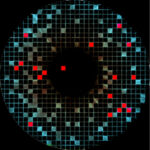

A brief history of seeing the invisible makes the connection between scientific discoveries in the 16th and 17th centuries and how they present us with the current paradox – that the same impulse that equipped us with the tools with which we visualize the virus today, also laid the foundations for its existence and proliferation. Looking closely at diverse examples, such as the work of structural biologist David Goodsell, whose Coronavirus artwork has received some attention from the press, a Coronavirus scroll from the Patua (scroll painter) community in West Bengal, India and canvases produced by artists of the Mutitjulu community at the base of the Uluru in central Australia, the essay shows how artists and communities move between the microscopic and mythical to find ways to understand and live with the virus. The same examples also expose connections between visual experiences of the virus and longer histories of colonialism, racism, and the circulation of propaganda. Using tracing apps and pattern recognition software to visualizing the virus as it moves through the population, raises questions about privacy and the surveillance state. In short, the essay elucidates the connections between art, science and global health and the political and racial import of these connections in lived experience.

You can consult the published essay here.