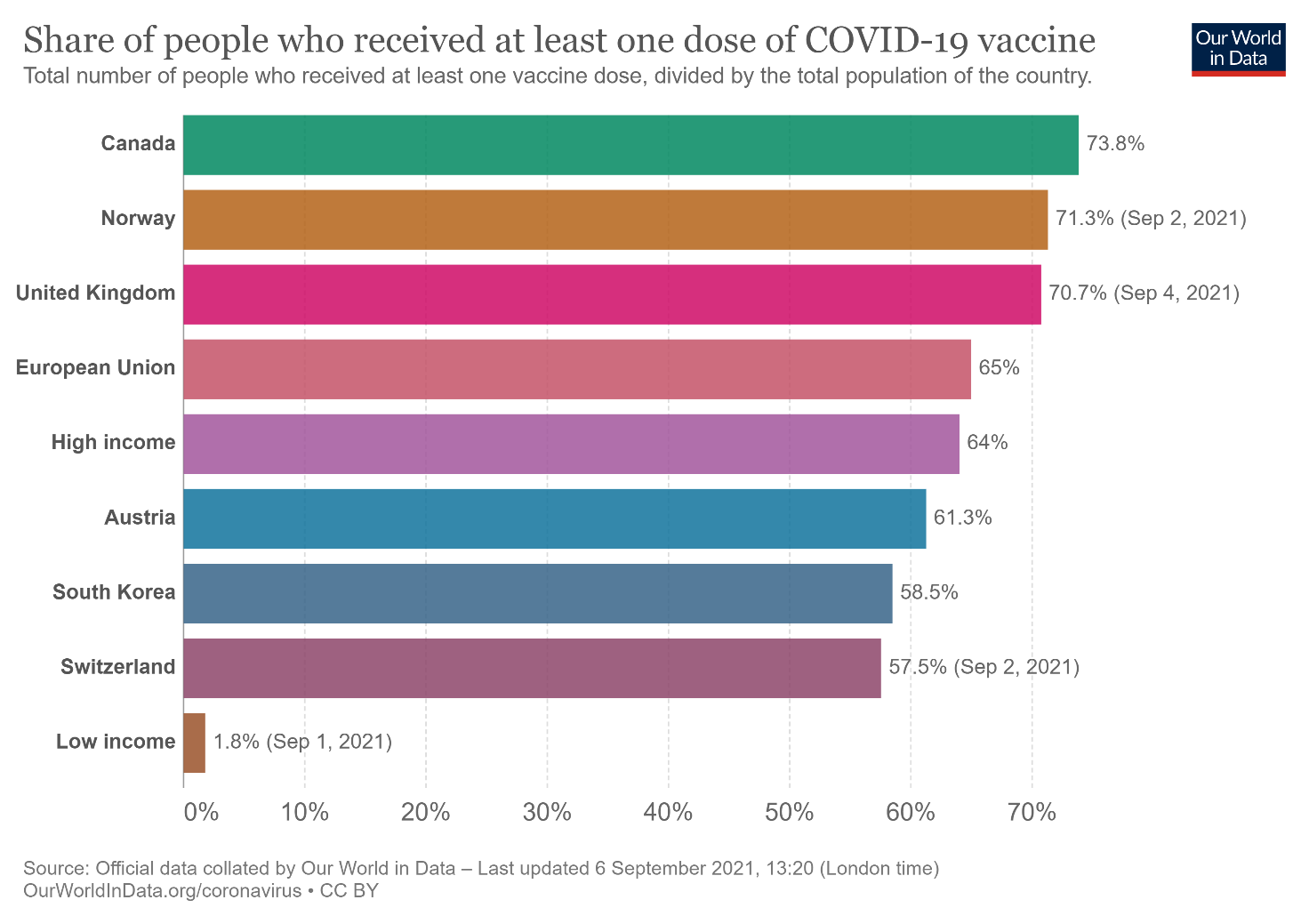

Current arrangements for achieving immunity against SARS-Cov-2 and preventing COVID-19 by vaccines is both epidemiologically short-sighted, and unjust. Taking their cue from Achille Mbembe’s theory of necropolitics, global maps of vaccine access bring into sharp focus the way in which social and political power results in deaths in the global south where vaccines are not available. The share of vaccinated populations is heavily weighted towards high-income countries, 10 of which have reserved 75% of the world’s vaccines. The brunt of vaccine capitalism is felt most in low- and middle-income countries, in particular countries in Africa; only 1.8% of people in low-income countries have had a single vaccine dose.

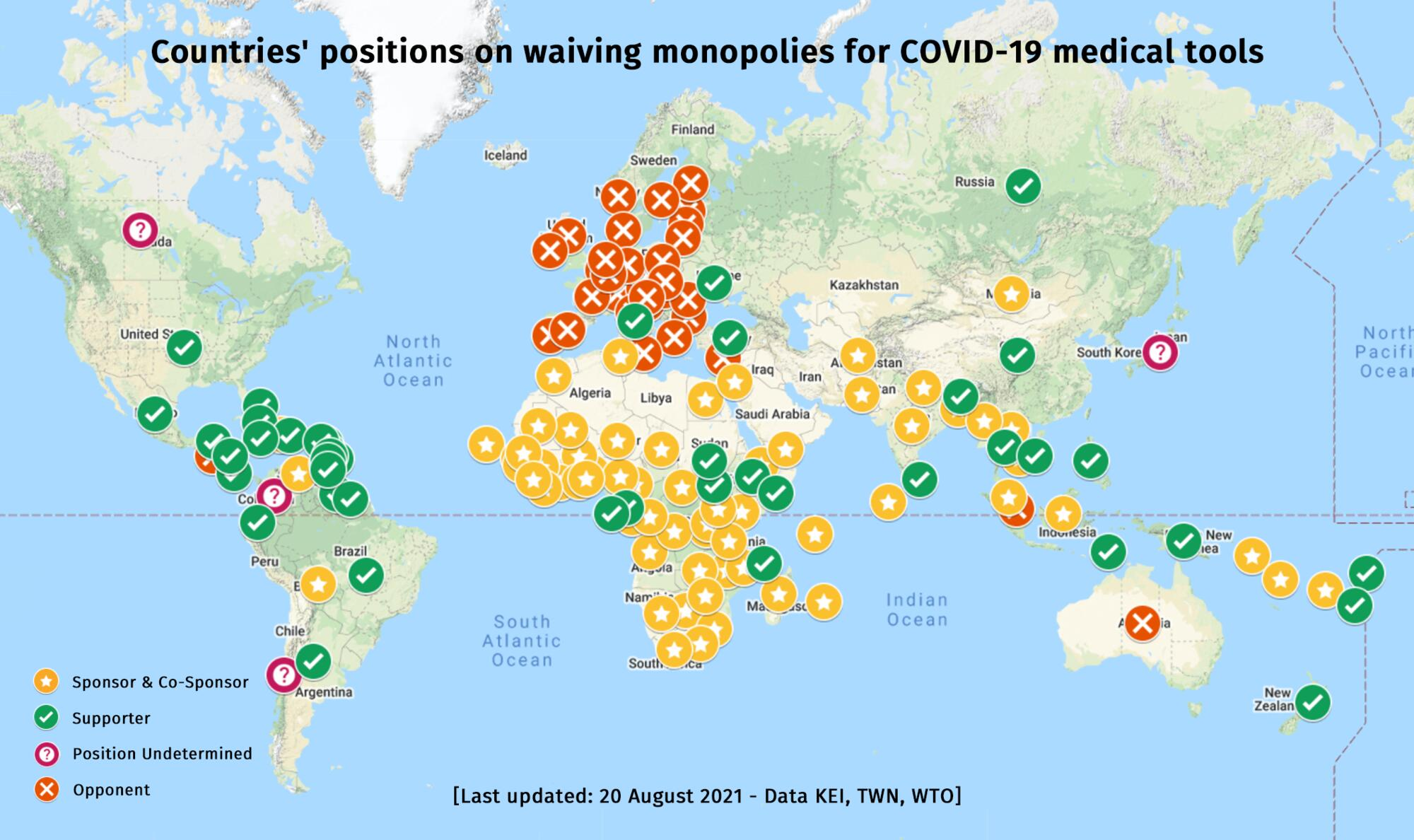

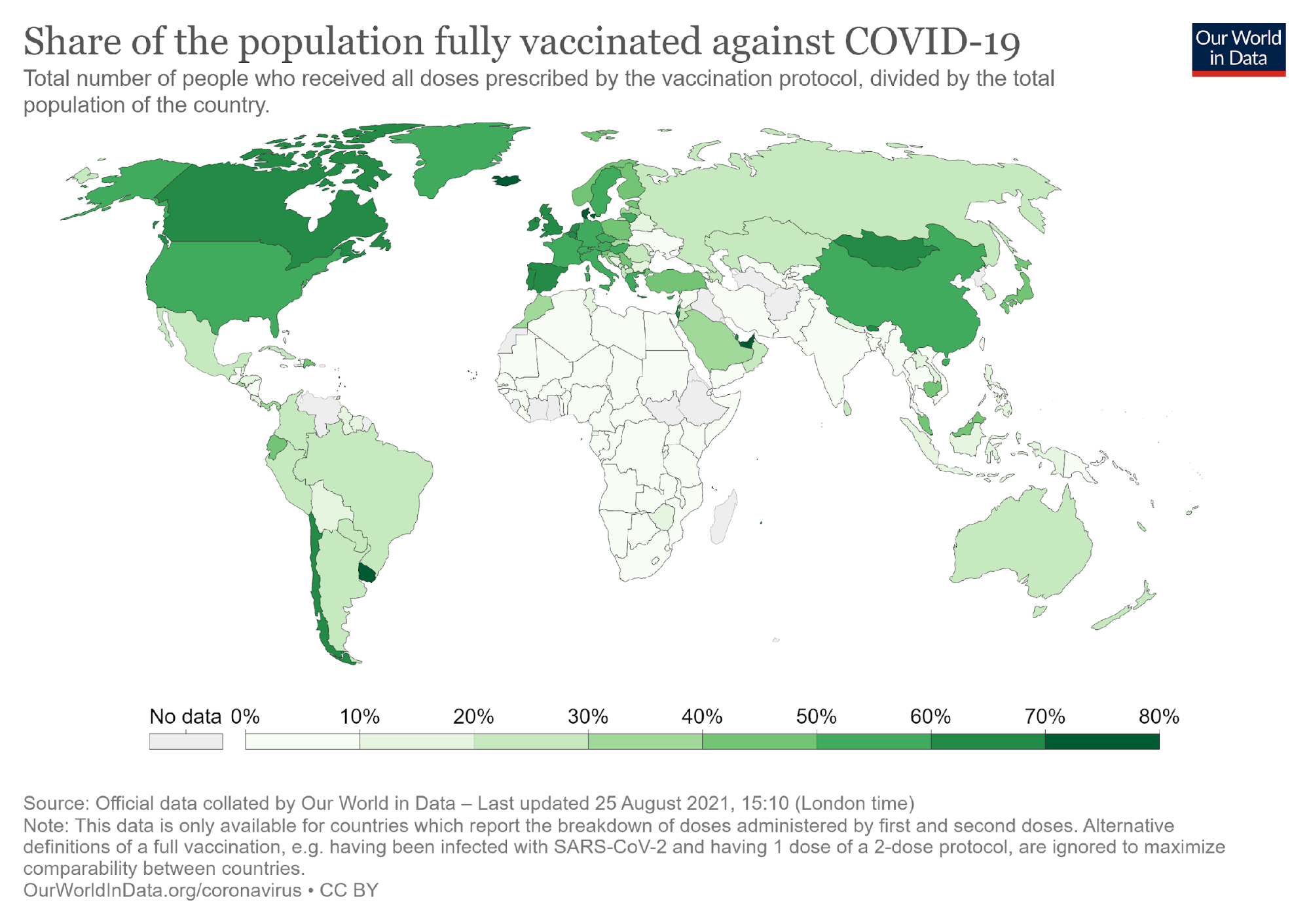

The map below visualizes the inequitable vaccine access that is a result of three strands of vaccine capitalism: exclusive patent regulations that protect pharmaceutical companies’ profits; proprietary contracts between countries and companies; and a smokescreen of humanitarian action called COVAX.

Share of the world fully vaccinated against COVID-19 on August 25, 2021. Map by Our World in Data. (Accessed 26 Aug 2021)

First, intellectual property rights legitimize the pharmaceutical industry to make exclusive decisions to whom vaccines are sold, and at what price. Under the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights Agreement (TRIPS) by WTO, companies that own the intellectual property hold the exclusive right to produce vaccines without competing generic products on the market. This way, they are able to keep prices high, as there is little competition from similar products. Vaccines currently on the market have been priced in such a way that developing countries cannot afford them. Prices may also vary depending on the contract: for example, contrary to any yardstick of social justice, the AstraZeneca vaccine was sold to South Africa at 5.25$ per dose but to EU at a lower rate of 2.16$.

Vaccine capitalism means that availability of vaccines at national level is made possible via bilateral pre-purchase agreements between vaccine producers and countries or regions, such as the European Union or the African Union. The African Union, with the help of the African Export-Import Bank, has negotiated an agreement to pre-finance 670 million doses of vaccine. While African countries are pooling their funds, very few low-income countries have contracts that would provide sufficient volumes to cover their entire populations. Countries are not on an equal footing on funding and networks in the negotiations, and the African Union has been given low priority.

The COVAX programme allows high-income countries to pretend they are involved in a humanitarian programme to ensure equal access. Any assumption that this is really happening is flawed. COVAX was established in April 2020, ostensibly to alleviate the need for vaccines in developing countries. COVAX is funded by various philanthropic funders and wealthy countries; it allows countries that have invested in it to secure vaccines for 20% of their population and any excess funds are used to cover vaccines for populations in developing countries. Through this programme, rich countries such as Canada have grabbed five times the number of vaccines required to cover its entire population. A small fraction of vaccinations have been made available in Africa via the humanitarian COVAX programme. Due to the pace of manufacturing, the surplus enjoyed by some is won at the expense of others. There is an inherent inequality in access being determined by the purchasing power of the countries where people happen to be born. This fundamental dynamic underscores how COVAX is, by design, unable – or not intended – to remove vaccine inequalities; in fact, it serves as a pretense for global access without delivering on its promises.

COVAX also acts as a smokescreen for the intellectual property rights issue at the heart of the inequity of vaccine deployment. India and South Africa proposed to the World Trade Organization in October 2020 that a waiver of intellectual property rights should be mandated to guarantee international availability of vaccines under the exceptional circumstances caused by the pandemic. This motion is presently endorsed and supported by over 100 countries, shown on the second map: the Africa Group and the Least Developed Countries Group; and now also includes the United States. It is advocated by organisations like Medicines Sans Frontiers, People’s Vaccine, Third World Network, and the European United Left at European Parliament. The map shows the extent of vaccine necropolitics – the relatively few but powerful countries opposing the waiver in order to protect their pharmaceutical industries.

The patent waiver is objected at the WTO by European Commission, UK, Switzerland and Norway; among other countries whose portion of vaccine coverage is high, Canada and Australia remain ‘undecided’. These countries ultimately protect the interests of Big Pharma and its profit-based approach, rather than the interests of the public. While the proposed waiver is time-bound and restricted to products related to the pandemic, a more radical reform could have profound impacts on how innovation is organised in the future, by questioning the capitalist modus operandi of vaccine production.

You can read the full article here: Sariola S. Intellectual property rights need to be subverted to ensure global vaccine access. BMJ Global Health 2021.