Visualizing

the Virus

On April 4, as Ontario’s third wave of the pandemic was getting out of control, Dr. Michael Warner, who is Medical Director of Critical Care at the Michael Garron Hospital, shared the story of one of his COVID patients on CBC News (with the family’s permission). He was interviewed twice that day. At first, his patient was in critical condition but still alive. Later on that same day, she died. Shortly after, he was interviewed by Natasha Fatah.

Until then, no personal COVID story of the sort – let alone of a patient who had just passed away – had been shared on national TV by the medical doctor in charge of the case.

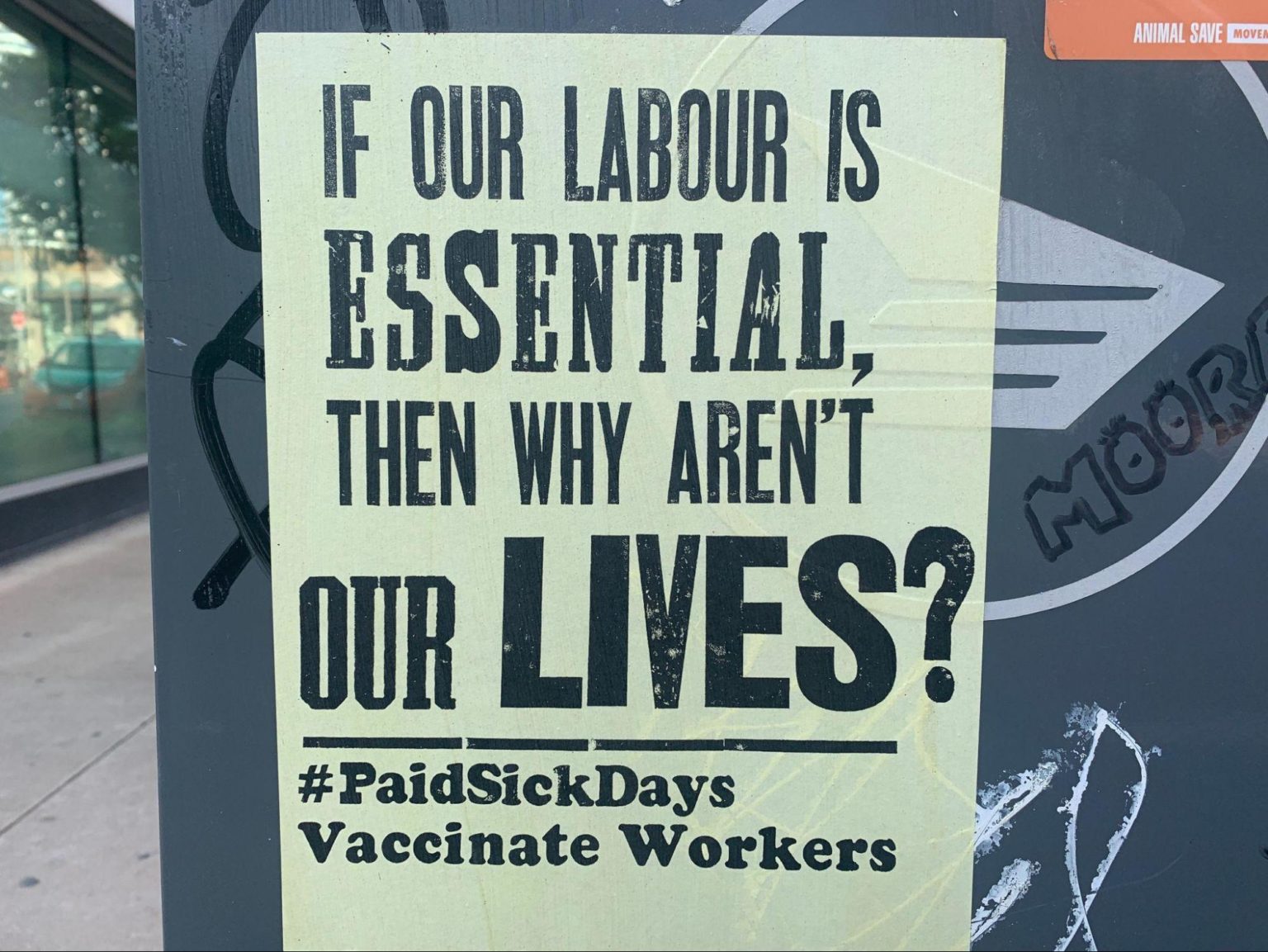

Dr. Warner’s patient was a working-class, racialized mother. Her husband, a factory worker, had caught COVID-19 at work. Despite an outbreak having just taken place there, the employees, who live paycheck to paycheck, were told that they were not eligible for sick days and therefore expected at work. As a result, all of them caught the virus and infected members of their households.

The first time we watched this interview, we instantly thought it might be a watershed moment in public opinion. Could a doctor sharing his deceased patient’s story impact the response of the government of Ontario to the third wave of the pandemic?

As it turned out, it did.

Dr Warner’s interview went viral. The public outrage at the preventable death of this patient was so strong on social media that it led University of Toronto Epidemiology Professor David Fisman to write this tweet.

Fascinating as it was, the response was not surprising. Indeed, while statistics, charts, and data have been used extensively by the media throughout the pandemic, they cannot match the ability of a human story to touch the heart of an audience. As Dr. Warner confessed, “we’re immune to these numbers”, but the sick “are real people”.Through his account of how he and his team failed to save his patient, Dr. Warner exposed not only medicine’s shortcomings but also the human cost of Doug Ford’s self-serving handling of the pandemic. CBC’s audience – and especially its White privileged members who can work from home – found themselves confronted with their collective failure to care for the most vulnerable members of their community. As such, his interview was a tour-de-force of tragic storytelling.

In the interview, Dr. Warner literally gives voice (through words, tones, silences, and sighs) to the politically voiceless, who his patient and her family represent:

“I just know that she doesn’t look like me. She’s a racialized Canadian who’s in her mid-40s, who has a family, and whose husband is working very hard to provide for his family; whose daughter spoke the best English of their family, who I tried to update most consistently and translate to her father. And their life will be forever altered by this experience.

They didn’t get to see her, from the moment that she entered the hospital. They’ll never see her. And the closest they got was a zoom meeting while she was in the prone position on a ventilator. That’s the closest they got.”

We don’t know whether Dr. Warner has ever taken classes in Classics or appreciates tragedies as an artistic art form. What we do know, however, is that he understands how the pandemic is, fundamentally, a human tragedy.

In his 4th c. BCE treatise on Poetics, Aristotle defines tragedy in those words:

Tragedy, then, is mimesis of an action which is elevated, complete, and of magnitude; in language embellished by distinct forms in its sections; employing modes of enactment, not narrative; and through pity and fear accomplishing the catharsis of such emotions. (Poetics 6, Stephen Halliwell 1995 transl.)

There are several tragic protagonists in Dr. Warner’s story: The husband, his wife, their daughter, and Dr. Warner himself. In all cases, the pain, suffering, loss, death, and bereavement stem from bad decisions. However, while Greek tragedy generally has the hero make the bad decisions that trigger a downfall, in this present case, viewers are at a loss to blame any of the protagonists. Rather, as they pity the victim and her family and witness Dr. Warner’s trauma, they are forced to reckon with their own collective failings.

To David Scott, “tragedies do not simply happen. They stem from the actions of agents acting in the potentially rival actions and in circumstances over which they can, in the end, exercise only partial and unstable control” (p.34). Dr. Warner’s inability to keep his patient alive despite the trust her family had in him is a raw manifestation of that fact; actions that are imitative of, and therefore also affect, the wider world (what Aristotle calls mimesis) thereby trigger within the viewer another layer of pathos. The ‘public’, normally expected to trust the government, become aware of how this woman’s death, and the multiple traumas it has engendered, is the direct result of its rulers’ political neglect:

“[The family] have never met me. Maybe they’ve seen me on TV but they’ve never met me. And they trust me, well they trusted me, to save her. And from the moment I told them that she had to be intubated to the moment I told them that she had to be proned, that is put on her belly, to the moment when I said that I have to send her somewhere else cause I can’t help her, they trusted me… And I’ll never meet them. But I will never forget her.”

Aristotle emphasizes how “tragedy is mimesis not of persons, but of action and life” (Poetics 6, Stephen Halliwell 1995 transl.). Dr. Warner’s oration warns us about a tragedy in the making: one where the hubris of a corporate and self-interested élite was about to lead to an otherwise preventable hecatomb. His patient’s story, which humanizes so many similarly preventable deaths, convinced the audience that for an even bigger tragedy to be avoided, a shift in political action was urgently, and morally, needed.

That day on CBC, Dr. Warner showed his deep understanding of the way White Supremacy had shaped Ontario’s governmental response to the virus. By sharing this story the way he did, he mobilized his own privilege and Whiteness in order to trigger change. His White, male, expert voice rendered the invisible plight of the GTA’s most hard hit communities both palatable and relatable to (White) privileged Ontarians. By making the invisible visible, and by naming the otherwise unnamed (who gets sick, how they look, how they speak, what they do, where they live, why they get sick, why they are dying more than the rest of ‘us’), he explicitly sought for a political reckoning and collective atonement:

“Her memory has to be a blessing and also has to be an inspiration. We got to take the politics out of this. We need to galvanize as a society. It’s not about lockdown or not… It’s about protecting people who keep us going. Bring the vaccines to the factories. Everything else needs to stop… Vaccinate everyone in Scarborough, everyone in Peel, everyone in North Etobicoke, everyone in Jane and Finch, everyone in Thorncliffe Park, cause that’s where the people live, who are dying.”

On April 6, that is two days after Dr. Warner’s CBC interviews, Ontario’s Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences released a damning series of data that showed how the wealthiest, and Whitest, parts of Toronto were the ones with the most vaccination points and the highest vaccination rate in the city, whereas the poorest, most racialized areas were, together with Peel region, the hardest hit yet least vaccinated ones (this is still the case as we write this post). This news fuelled public outrage towards the government. As the number of COVID cases and ICU admissions continued to soar, and amidst declining rates of approval, the government finally issued a stay-at-home order on April 7. This measure did nothing to improve the rate of vaccination in the most affected regions. Neither was it accompanied with a program of paid-sick days.

Dr. Warner’s story was impactful because, by centering the human, personal and tragic nature of the pandemic, he touched people’s hearts in a way that negatively impacted Doug Ford’s rate of approval. Yet his voice, and his patient’s passing, did not convince the Conservative Party to truly and meaningfully start to care about those whose lives were on the line. And so, as he and so many of his colleagues had predicted, things continued getting worse. Call it the Cassandra curse.

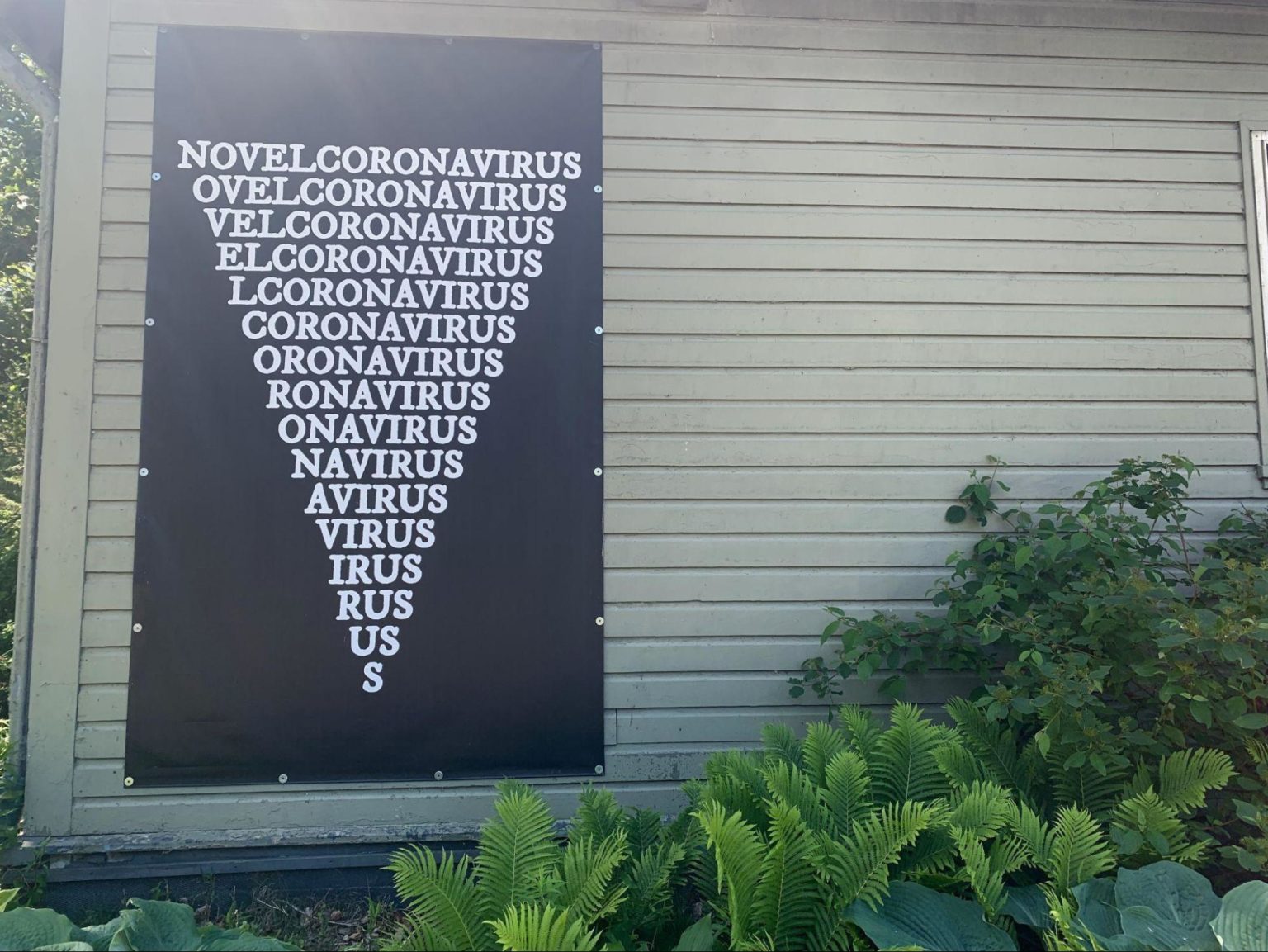

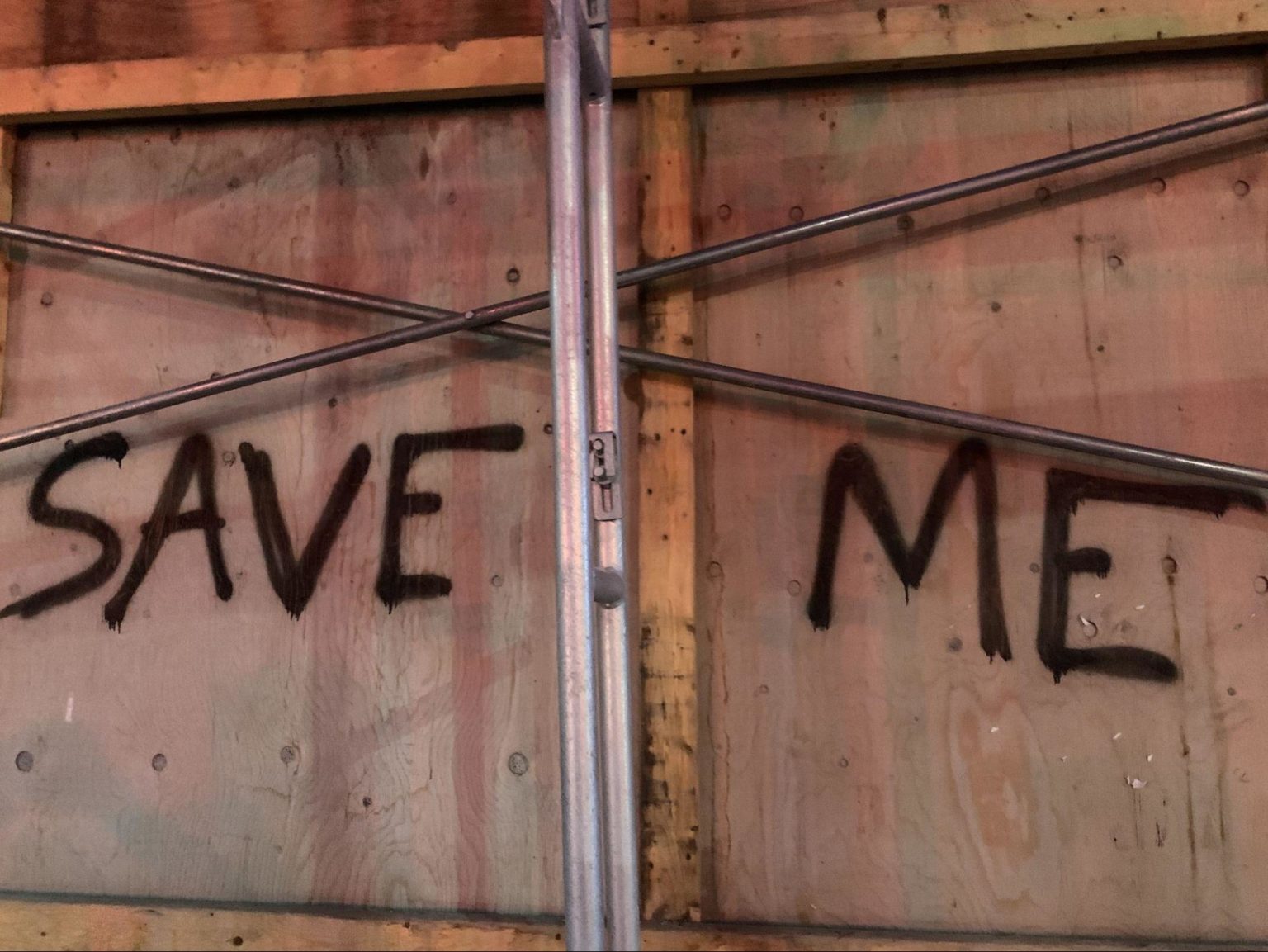

All pictures were taken by Katherine Blouin.