Visualizing

the Virus

“To be an individual mind or a critical voice is like suicide in China—it’s impossible. Art plays a crucial role in societies, but in China it never functions as it should due to current strict censorship laws.” – Ai Wei Wei

Chinese leaders faced two significant problems at the start of 2020: the rise of a population-threatening pandemic and a surge of outraged netizen voices. As COVID-19 spread from Wuhan to other provinces, thousands of public messages emerged on Sina Weibo and other Chinese social media platforms, angrily demanding to know if the local government was concealing yet another SARS-like virus. Several liberal-minded Chinese began to envision the impossible, as independent reporting gained online traction faster than the Chinese propaganda machine could handle. They began hoping that this tragedy would be a call to action, spurring the Chinese people to resist their authoritarian government. Perhaps now, they thought, the world’s most powerful propaganda machine would crumble after decades of worsening censorship and tightening ideological control.

Instead, the Chinese government has managed to control and manipulate the narrative to an unprecedented degree. Starting in February 2020, after heightened public outrage over the death of COVID-19 whistleblower Dr. Li Wenliang and a hospital publicity stunt by Xi Jinping, censorship increased over the Chinese internet as officials began an effort to shift public perceptions. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has long manipulated its history, successfully hammering the message to their people that unless strong hands are in control, the country will fall into chaos. Almost every part of the CCP’s most sensitive history, from the Cultural Revolution to the Tiananmen Square massacre, has been meticulously crafted. Party leaders quickly realized the danger of allowing public, unfiltered conversations around these historical events. Under the rule of Xi Jinping, the CCP has grown even less supportive of non-party approved perspectives, and the current pandemic narrative is no exception. Chinese state media has endeavored to promote materials spanning from TV shows to books to propaganda posters. All of these materials work to bolster public acceptance of the government’s positive narrative regarding Beijing’s pandemic response.

Particularly revealing of this overlap between public health efforts and political manipulation is the 中国新冠疫情政策宣传海报 (Chinese COVID-19 political propaganda poster collection) housed at the Princeton University Library.

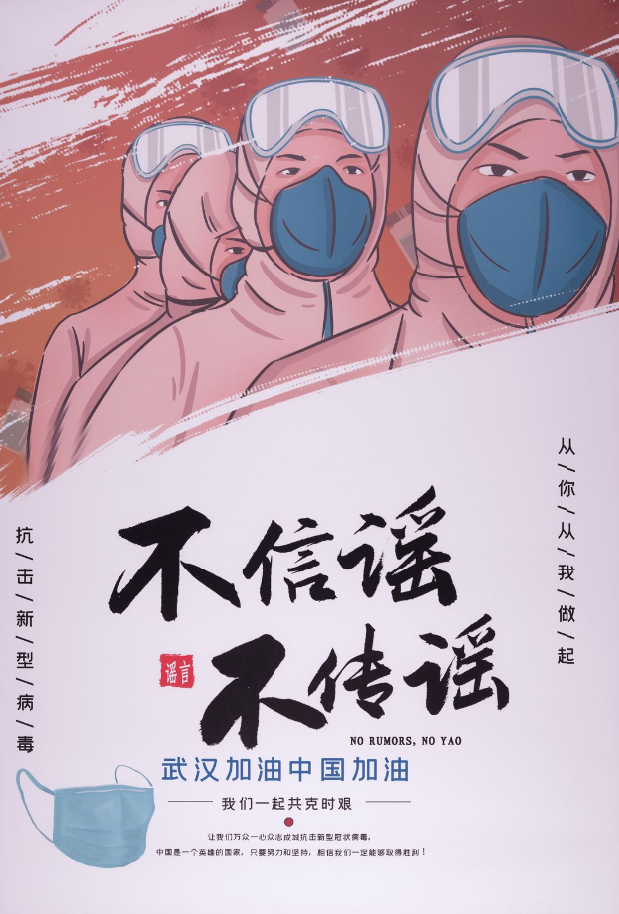

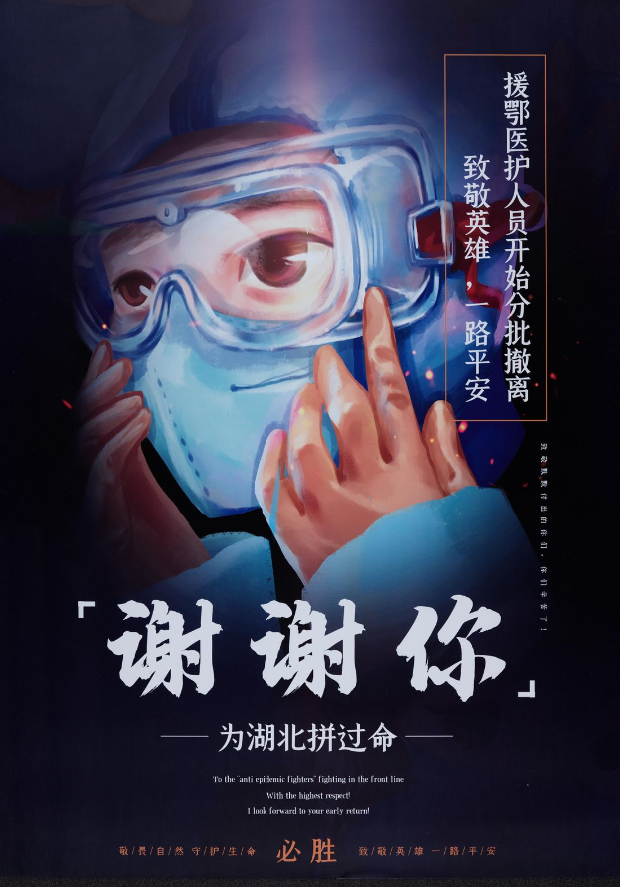

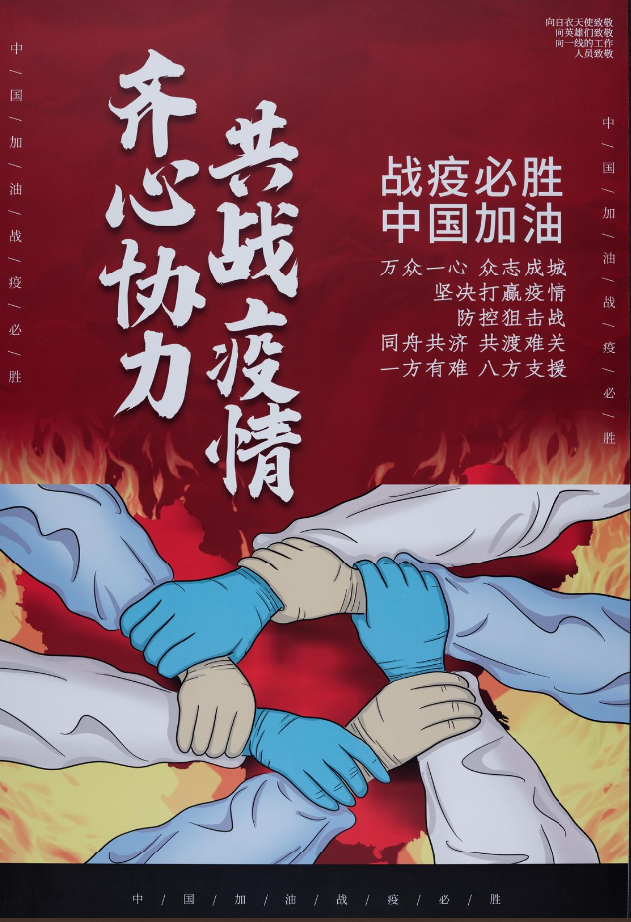

As a means of communication, the CCP has cultivated a number of common iconographies over the years. Authorities have created a ‘symbolic universe’ by operating with party and state media, and adapting elements of traditional Chinese art alongside pop culture. These symbols consist of a popular set of tropes serving as metaphors for the legitimacy of civil and state institutions. Each of the posters found in this collection reflect common language, from public health messaging (mask-wearing) to militaristic language (war on the epidemic and the fight against the virus). Moreover, the posters aim to visually appeal to popular opinion with their comic and manga aesthetics. They also depict imagery and slogans not dissimilar to CCP propaganda during the Cultural Revolution: symbolic heroism (front-line healthcare workers, epidemic soldiers, etc.), rallying cries (pleas for Wuhan to endure local hardship for the national good), their nationalistic proclamations and ideologies, use of common Chinese 成语 “chéngyǔ” (idioms) also found during the 1950s (眾志成城 “zhòngzhìchéngchéng” (united peoples can build a city)) and the intended tight control of public opinion (不信谣,不传谣 “bùxìn yáo, bù chuán yáo” (no spreading of rumors)). Each of these symbolic representations and references exhibit emotional governance in its simplest form. Media representations, therefore, are building blocks for the production of personal and institutional meanings, enabling viewers to consolidate nation, state, and crisis into a single narrative linked with deep-seated emotions.

Any China-watchers in future years will have to possess a thorough understanding of Beijing’s governance during the pandemic. China’s response to COVID-19 reflects Beijing’s heightened ability to control what its people domestically see, hear and think, and the Chinese political propaganda poster collection offers a perfect example of this. Thus, regardless of how Beijing manages the next crisis – be it a financial crisis, war or natural disaster – the party has already proven its capabilities to emotionally govern its constituents.

Below, I look at some examples:

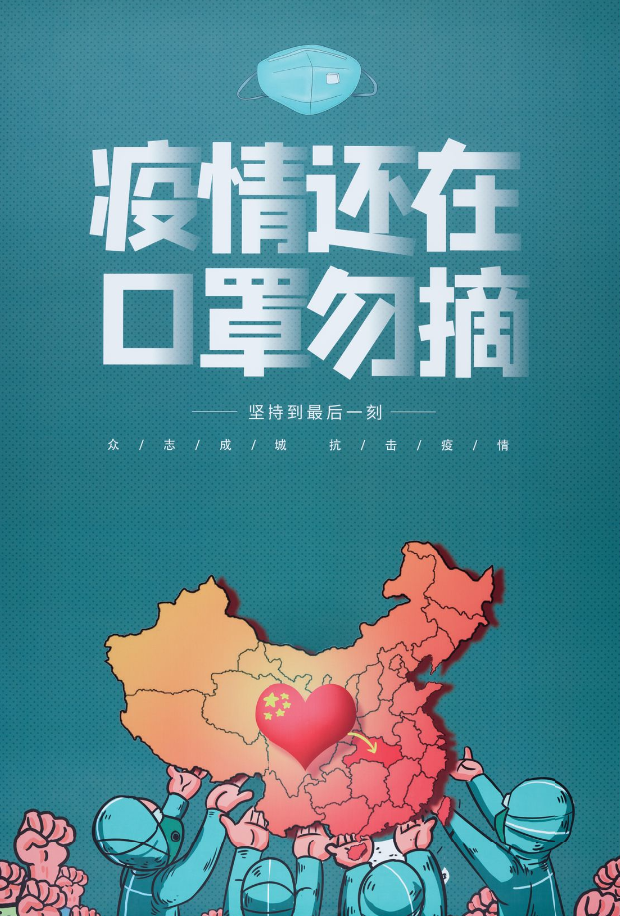

This poster marks the continuation of the pandemic and enforces mask wearing for constituents. There have been reports of public humiliation punishments by the police for constituents who don’t wear masks. Interestingly, the poster also includes Taiwan in their map of China. Taiwan’s system of pandemic management stands separately from China’s.

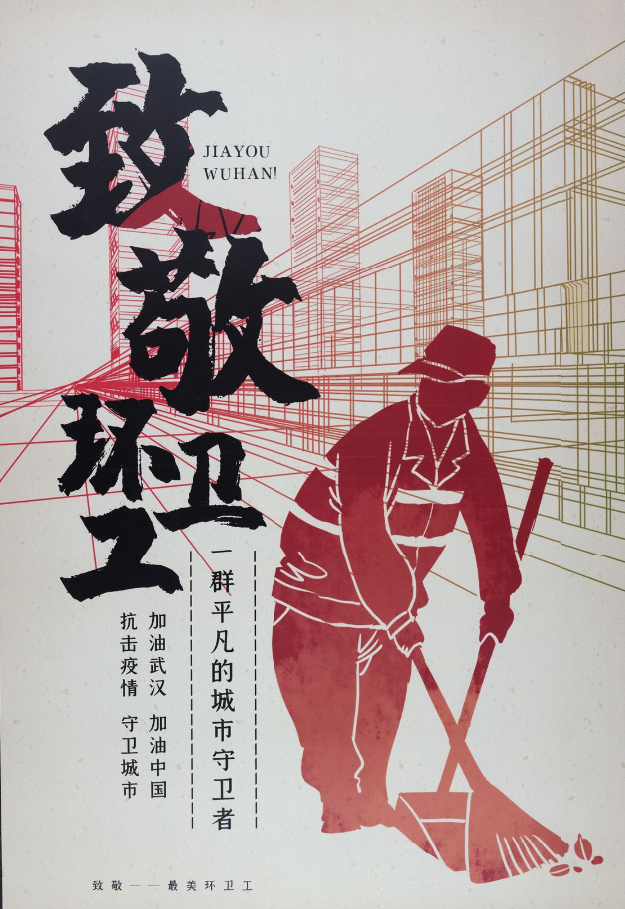

This poster calls for unity in Wuhan to fight against the pandemic. The poster is meant to reassure Wuhan residents that the government cares for their wellbeing. However, this encouragement and peaceful illustration contrasts the government’s initial response to the chaos of Wuhan’s outbreak, when hundreds died as the military locked down the city.

You can view the poster collection here.