In spring 2020, I wrote an article in response to two kinds of violence – verbal and physical violence, on the street and in the media – against anyone who looks Chinese or East Asian. Such behaviour was then, and still is, rampant. I myself have been shouted at by strangers in Berlin and I know others of Asian and East Asian heritage who have been verbally or physically attacked. This kind of anti-Chinese/Asian sentiment, invoking the stereotype of the dirty, savage Asian eating “bizarre” foods, also surfaced in the media back in February and March, when China and East Asia were in deep shit caused by the pandemic. Instead of sympathy for the tragedy that was unfolding on a daily basis, I saw this incomprehensible and cruel blaming of the victim: because we allegedly eat bat soup, we deserve to die.

The second kind of violence that prompted me to write that piece is for me equally, if not more worrying. It was being propagated by people who have some discursive power, or actually a lot of it: namely, epistemic violence. One example is a text written by Alain Badiou at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis. Published on March 23, it was immediately translated into Chinese on March 24. That’s the level of influence this writer has.

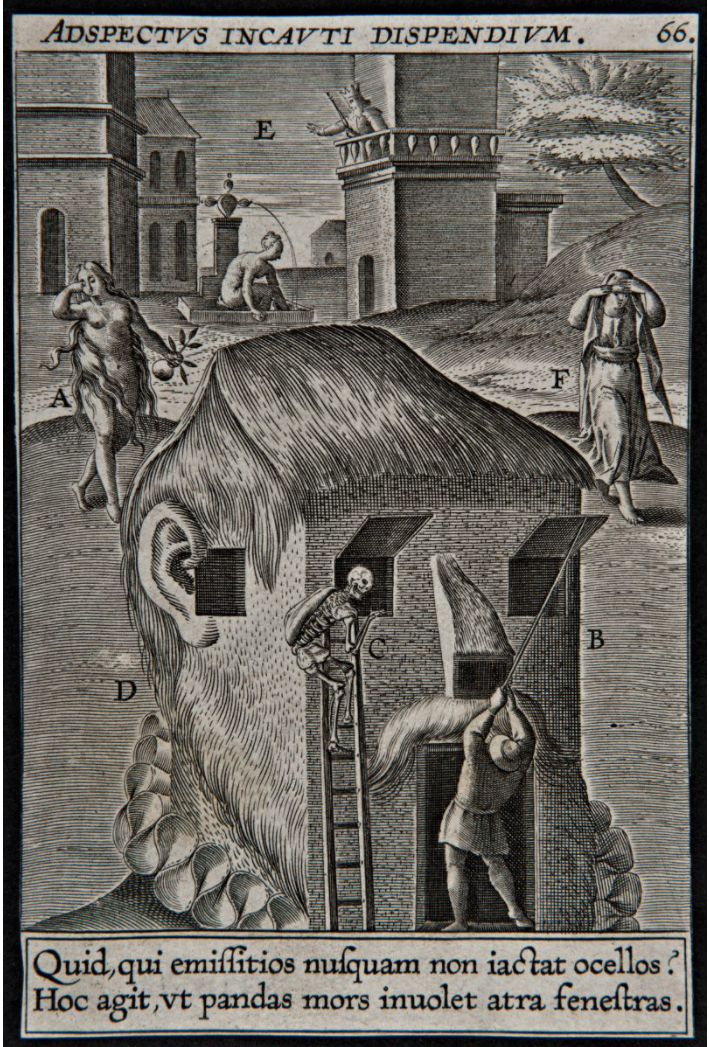

Engraving from Verdicus Christianus or A True Christian, for the chapter Adspectus Incauti Dispendium or The Cost of Careless Looking (Theodoor Galle) 1601

The central point of my response is that Badiou turns the question of hygiene into a question of taste and preference, by, for instance, citing “the irrepressible taste for the sale for all kinds of living animals.” In this way, instead of using his discursive power for good use, he effectively perpetuates a racist trope that he himself criticizes in the same text.

What I want to highlight is that, while wet markets are not hygienic according to the standards of western supermarkets, their so-called dangerous dirtiness is first and foremost an economic condition, and emphatically not a matter of taste.

And that’s only the entry point. These wet markets are probably among the few remaining places that are at the periphery of global capitalism, which desperately tries to incorporate them into its systems.

I grew up in a community served by the type of wet market that has been and continues to be grotesquely misrepresented and hated. This background spurred me on to articulate my response to misrepresentation, street violence and epistemic violence.

The woodprint illustration appears in Veridicus Christianus (A True Christian), published in 1601 and was accompanied by the caption: “The Cost of Careless Looking.” The image shows the dangers of a curious gaze penetrating into a person’s home. It was believed that the orifices of the body, and by extension the openings of the house and the borders of the village, should be carefully guarded against intruding dangers.

This article, originally published in OpenDemocracy on 6 April 2020 under the title “COVID-19: on the epistemic condition”, brings into sharp relief how ongoing stereotypes of the wet markets of Wuhan obscure a much longer and deeper violence driven by Anti-Asian racism and global capital.