As cases of a new and poorly understood viral infection began appearing in the United States in early 2020, the Trump administration was confronted with an inconvenient truth. While the emergence of the novel coronavirus promised a cascade of real-world “wicked problems”, it was also an impending public relations disaster. Harsh lockdown measures had stemmed outbreaks in Wuhan, but such stringent restrictions would—it was intuited—be so politically unpalatable to Americans that community transmission was inevitable. Cynically, the challenge ahead would lie not in containing the spread of a fast-moving pathogen, but in selecting which facets of its reality to acknowledge.

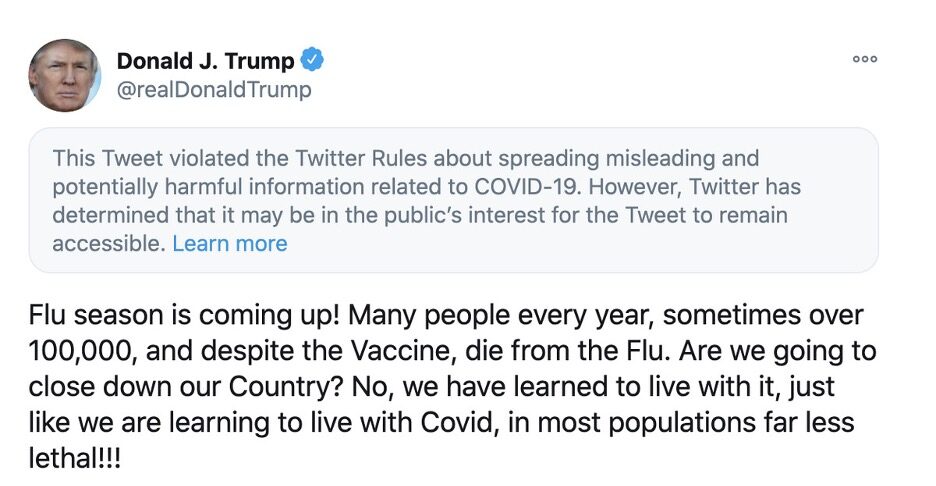

Attempting to head off threats to its political survival, the administration rapidly crafted a manipulated account of the new virus: one that consistently minimized its potential impacts on individual and public health. Within a remarkably short time, non-evidence-based views about the novel coronavirus, its epidemiology, and the prospects for its prevention and treatment began proliferating. As a study would later establish, the largest driver of pandemic misinformation in 2020 was the President himself, who relentlessly conveyed conspiratorial and anti-scientific messages in official briefings and via social media.

Almost from the first signs of its emergence, the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States has thus furnished the venue for a high-stakes ideological contest over authority, legitimacy, and even reality itself. Zero-sum struggles over the meaning of the pandemic have helped underwrite patterns of denial, misdirection, cognitive dissonance, and magical thinking. As I’ve written elsewhere, Americans may have been particularly prone to these perceptual weaknesses, given the influence of exceptionalism in the nation’s cultural politics and our tendency to misremember some of our most serious collective mistakes. And as I discuss in my contributed essay, the politically driven project of whitewashing the virus reached its logical conclusion in discourse about COVID deaths—the most inconvenient truth of all.

Though fatalities from an acute respiratory virus might superficially seem like one of the least negotiable realities of the pandemic, COVID mortality rapidly became a prime site for manufacturing doubt. Death counts and infection fatality rates have represented a site of pointed ontological, epistemological, and ideological disagreement in the U.S., and experts as well as laypeople have achieved remarkably limited consensus regarding what constitutes a death from COVID-19, whether deaths are being tallied accurately, and what the social significance of these deaths might be.

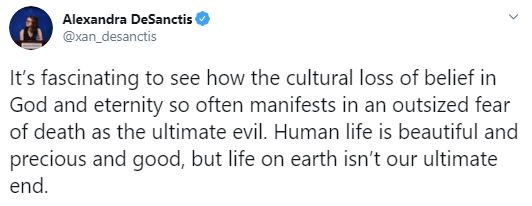

Coining the term necrosecurity, my essay attends to a form of pronounced, even performative indifference towards death and dying that began manifesting during the early months of the American pandemic. As I suggest, statements by the administration and its allies regarding COVID-19 (and comments by some nominally left-wing sources as well) were marked by a sociopathic sangfroid—as if the earliest victims of an epochal crisis were of no concern to anyone. With hardly a moment of silence or a mention of thoughts and prayers, right-wing media figures called for the lifting of public health measures, dismissing the risk of infections and disparaging the dead.

An ethos of accepting death—or of a nonchalant attitude towards certain deaths—has plenty of precedent in the United States, of course. One historical analogue for the experience of COVID-19 is the experience of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. After Katrina, right-wing commentators and politicians as well as mainstream media represented the survivors of the hurricane in harshly dehumanizing terms, imagining them to be violent and immoral “looters”, “parasites”, and “drug addicts”. Cultural critic Henry A. Giroux describes these representations in terms of a biopolitics of disposability: media tropes about “looters” conformed to a worldview in which “the poor, especially people of color, not only have to fend for themselves in the face of life’s tragedies, but are also supposed to do it without being seen by the dominant society. How else to explain the cruel jokes and insults either implied or made explicit by Bush and his ideological allies in the aftermath of such massive destruction and suffering?” (2007, 175-176). Cruel jokes and insults about COVID-19 deaths accomplish a comparable kind of cultural work—trivializing the violence of the pandemic while making space for more of the same.

Though the tenor of official messages about the coronavirus has become more sober and civil under the Biden administration, some aspects of U.S. pandemic policy continue in the vein of necrosecurity. In diverse jurisdictions, a lack of political will to implement non-pharmaceutical interventions like masks and social distancing is evident. At-risk cohorts—including unvaccinated schoolchildren—are neglected in policy. Federal agencies have permitted states to manage the pandemic in dangerous and discriminatory fashion, and the public has been steadily pressed back towards business as usual. As the pandemic progresses, Americans will also need to resist seemingly “kinder, gentler” policies that tacitly sanction preventable death.

You can read the full article here.